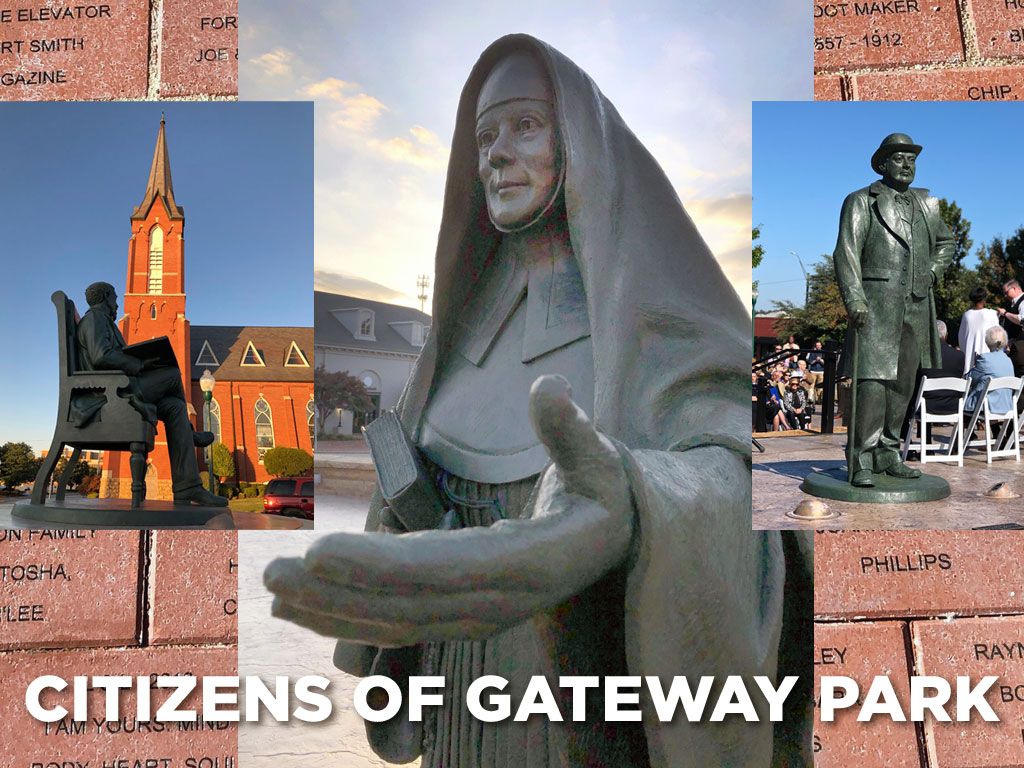

Dedicated last month to the City of Fort Smith, a new park at Rogers and Garrison Avenues is a visual gateway to downtown and, historically, a gateway to both the past and future. It has three permanent citizens.

Judge Isaac C. Parker selected for more than his judicial record

In the center is Isaac C. Parker, whose judicial record is well-told at his courthouse that is now Fort Smith National Historic Site, his judicial bench in our Museum of History and in the annals of history.

But this statue also praises Parker as a civic leader. Though it is hard to imagine how he spared the time from his vast federal jurisdiction that included the Indian Territory, he was also a family man, deeply involved in the community. He was a founding board member of St. John's Hospital, later Sparks Regional Medical Center, now Baptist Health-Fort Smith. He joined the local fraternities of Odd Fellows, the Border City Knights Lodge of Knights of Honor and the Grand Army of the Republic.

He was president of the Fair Association and the Social Reading Club and with his wife, Mary, helped create a library. Perhaps his most important outside commitment was to public schools, as a school board member and by leveraging his political influence to help obtain a federal land grant.

Honored guests at the park dedication Oct. 17 were Parker descendants. Great-grandson Charles Parker of Catoosa, Okla., thanked the 64.6 Downtown park creators for emphasizing Parker’s citizenship. He shared that he once was excused from jury duty by saying he was descended from “the Hanging Judge,” for which his father, Isaac Charles Parker, chided him, ‘because he was so much more to the city of Fort Smith.’

“I was so happy that his other civic accomplishments such as education were brought out in the dedication,” Charles Parker wrote to 64.6. The values of justice, education and heath care to citizens are symbolized in all three statues.

A once-faceless Sister of Mercy now represents all of her Irish order who came to Arkansas

In a lifetime of devotion to the duties of her faith, Sister Mary Teresa helped lay the foundation of both education and health care for Fort Smith and Arkansas.

Alicia O'Farrell was born in Ireland, in ancient Naas Parish, County Kildare, Province of Leinster, near Dublin. She entered the Convent of the Sisters of Mercy in Naas under the religious order’s founder, Venerable Mother Mary Catherine McCauley, and received the white veil and the name Sister Mary Teresa.

She was described as a tall, fair and well-built woman with large blue eyes and a pleasing personality. As no likeness of her exists, sculptor Spencer Schubert imagined the statue’s face.

In 1850, she left for America with Bishop Andrew J. Byrne, who had charge of the new diocese of Arkansas and the Indian Territory.

Byrne had purchased 640 acres of surplus federal land in Fort Smith, including old Cantonment Belknap, at the head of what is now Garrison Avenue. On March 6, 1848, he had dedicated the town’s first Catholic church, a small log building on North Third Street. St. Patrick’s would last until the outbreak of the Civil War. To serve his remote parish, Byrne chose Mother Superior Mary Teresa; Sisters Mary Agnes Greene, Mary DeSales O’Keefe, Mary Stanislaus Farrell and five postulants.

They crossed on the “John O’Toole” with other Irishmen bound for Arkansas, landing in New Orleans on Jan. 23, 1851, and continuing to Little Rock aboard the steamship “Pontiac.” There, the sisters opened a day school, Mount St. Mary Academy, today the oldest educational institution in Arkansas.

In January 1853, Mother Mary Teresa and half the women came by steamboat to Fort Smith. In a former military building at Fort Belknap, they established St. Anne Academy for Girls. They taught the pupils, as well as fulfilling all their other duties.

In 1858, Mother Mary Teresa moved to Helena, Ark. to open St. Catherine’s Academy. The Civil War changed the academy's mission. Schools became hospitals where the sisters nursed soldiers of both armies, as well as any others in need. She cared for Bishop Byrne until his death on June 10, 1862.

In 1868, she returned to St. Anne’s Convent in Fort Smith until her death on Jan. 16, 1892. She is buried near her sibling, Sister Mary Baptist Farrell, and Sister Mary DeSales O’Keefe in Calvary Cemetery near Gateway Park, which is within Byrne’s original land purchase. The towering Immaculate Conception Church, which her statue faces, was not dedicated until 1899.

For all of their accomplishments, little more is known of Farrell and her Irish Sisters of Mercy. But at the park dedication, Sister Chabanel Finnegan represented their order’s continuity of charitable work here, Mercy Hospital at the forefront.

These resilient women of faith gave Arkansas and this city the earliest of many Catholic schools and hospitals that have benefited the people of the city and which serve still.

John Carnall, father of Fort Smith Public Schools

No person worked longer to create a proper public school system for this city than John Carnall, now honored with a statue at Gateway Park. Though less famous than Isaac C. Parker or as enduring as the Sisters of Mercy, he is as worthy a historical figure, for many reasons.

Over more than 40 years, he persevered to establish a sustainable public school system. The source of funding he won also provided the capital that fueled Fort Smith’s growth.

Although Carnall held elected office, published newspapers and prospered in real estate, it is in connection with schools he was chosen as a statue.

A teacher, but no reliable schools

Carnall came to early Fort Smith in 1840, at the age of 22, to open a school. It was financed by a $500 investment by John Rogers, a pioneer Fort Smith citizen who was determined to leverage the presence of the military fort to build up a prosperous city.

Carnall had been educated as a teacher and had three years of experience teaching in Manassas, Va. He conducted that first school (for white children) on North 3rd Street and Garrison Avenue. The town’s few streets had been platted by Rogers, parallel to the river and opposite the fort’s gates. Rogers personally underwrote many ventures to encourage the young town to grow. But the school was closed when Rogers’ investment money ran out.

In 1845, Carnall and his wife’s sister opened a private Fort Smith Academy in a large house on North 6th Street, naming the building Belle Grove. After a few years, that school building was leased to other teachers. Pupils paid tuition.

City, county and state booster

Carnall turned from the classroom to make a living. He worked as a surveyor for Crawford County, which then included Sebastian County. In 1846, he was elected county sheriff. Re-elected to two more terms, he then was elected in 1851 as the first County Clerk of the newly created Sebastian County, serving until 1857. As clerk, in 1851, he built a 16-foot square, log courthouse in Greenwood, Ark., the first county seat. His lifelong effort to bring roads, bridges and railroads here began then.

In the 1850s, he started investing in land and ownership of The Herald, a newspaper founded by John Foster Wheeler in 1847. Carnall and Wheeler used their increasing influence to promote Fort Smith and both became as active as their mentor, John Rogers, who died in 1860.

At the outbreak of the Civil War, Carnall was elected to the Arkansas (Confederate) legislature. In 1863, Fort Smith was taken by Union forces.

Post-war, Carnall resumed publishing The Herald by 1866, reporting on the contentious Reconstruction government. War refugees crowded into town, emancipated slaves and impoverished white families who came in from the countryside.

In 1868, the state legislature mandated public education, to be supported by state script.

Newspapermen Carnall and Wheeler joined to fight additional taxes the Reconstruction government imposed on citizens, who were still ruined financially by the war.

Public schools were opened in 1869, one for whites and one for black students. The school for blacks had been built by the federal Freedman's Bureau in 1868. White children studied in a leased building until 1870, when the school board purchased Carnall's wooden Belle Grove building for $10,000. In 1874, these public schools closed due to the failure of the state script, which could not be redeemed for full cash value.

A sustainable funding source was badly needed.

Brilliant idea; years of lobbying

In 1871, Carnall had spotted a possible solution. He had returned to Virginia to see his dying father and visited Washington, D.C., where he learned that the federal government intended to dispose of surplus military reservations. On the list was the Reserve, some 306 acres originally purchased from John Rogers for the site of the second Fort Smith. Carnall launched a campaign to get this land given to the city.

He contracted with the city council for authorization to lobby Congress, at his own expense. If he failed, the city would owe him nothing. If he succeeded, he would eventually be repaid one-fourth of the value of the property received.

On Nov. 27, 1871, the city authorized “efficient and influential counsel” to draft bills to present to Congress. Lawyer Henry E. McKee worked in Washington, while Carnall made many trips between Fort Smith, Little Rock and the capital.

It was an uphill battle for more than a decade as Carnall tried every means to pass a bill.

He got the help of Sen. Powell Clayton, the former Reconstruction governor Carnall had once fought, and U.S. Attorney General Augustus Hill Garland, also a former Arkansas governor.

He worked with Arkansas U.S. Congressmen J.E. Cravens and John Henry Rogers. Attorney Benjamin T. DuVal and Judge Isaac C. Parker advised him wisely in strategy.

Congress acted in Fort Smith's favor in 1884, conveying acreage bounded by Garrison Avenue to the Poteau River and from the Arkansas River to South 4th Street. Because of this gift, the Fort Smith “Special School District” was created – and authorized to sell the Reserve property.

The agreement specified that money from the sale of the lots could not be spent directly to build school buildings. Therefore, the lots were sold on credit at 8 percent interest and school construction was financed from the interest collected.

At the time, the Bank of Western Arkansas, later to be renamed First National Bank, had a reserve of $200,000. But soon after the sale of the lots commenced, the school board took in almost half a million dollars.

The availability of this school district capital sparked one of the biggest building booms in the city’s history, funding the construction of some of its largest downtown buildings. Many still stand.

This ingenious funding, obtained by Carnall, was the foundation of a sustainable public school system – the same Fort Smith Public School District that exists today.

New, brick school buildings were erected, such as the fine brick Belle Grove School and later, the magnificent Fort Smith High School. Equipment and textbooks were purchased and teachers hired. Our school system was superior to any in the state. Floating on a sustainable cash reserve, the Fort Smith Special School District was the envy of the region and the powerhouse of education that continues into the 21st century.

Always boosting and building

Carnall invested in his city for the rest of his life with purchases of stock in the Fort Smith Loan Association, the Fort Smith Oil Trust, the Fair Grounds Association and the Fort Smith Academy of Music.

In 1872, after the death of his brother and sister-in-law, Carnall brought his two young nieces, Ella Howison Carnall and Annie Lee Carnall, to live with his family. Ella was an excellent student and entered the new Arkansas Industrial College, later renamed the University of Arkansas, in 1877. After her graduation in 1881, Ella was an associate professor of English and modern languages. She died in 1894 at the age of 32. Her popularity was such that in 1905, the first women’s dormitory was named for her. Today, it is known as the Inn at Carnall Hall.

Carnall accumulated land in Fort Smith, Sebastian County and 15 other Arkansas counties and in Texas. He created new subdivisions, selling lots for $10 down and $2.50 per month, which expanded the footprint of the city.

He used his presses constantly to publish many articles and pamphlets marketing Fort Smith and Western Arkansas. While investing in fruit farming, he advertised the fertile soil and beneficial climate of the region for growing commercial fruit crops, such as apples.

He was involved in three newspapers: publisher of the Fort Smith Herald in 1866, co-founder of the Western Independent in 1871 and the Fort Smith Elevator in 1878. On the masthead of that paper were these words:

“Yes, while I live, no rich or noble Knave

Shall walk the world, in credit to his grave.”

The Elevator was published from 1878 until 1909 and became The Weekly Elevator.

Carnall's charming home is still standing at 402 South 14th Street, a few blocks from Gateway Park. Next door at 410, he built a three-story, double “tenement house” in 1888. That early apartment building also endures today.

Chronic asthma dragged the aging Carnall into decline. On Feb. 16, 1892, he had a good day of health and enjoyed a visit with two sons and his brother-in-law. After stepping to the porch to say goodbye to his last visitor, he began to gasp for breath and was helped back inside. He died quickly, as his wife held him. He was 82, and had spent 60 years championing Fort Smith.

Carnall’s legacy

In 1962, the Fort Smith Special School District named Carnall Elementary for John Carnall.

Except for researchers, who will find many deeds of Carnall in historical newspapers, fewer and fewer people have learned about his significance, until the statue project.

Carnall’s statue at Gateway Park is fitting, because also he can stand for progressives like him – those who think beyond their own pockets and act on the belief that a rising city lifts all.

During the quest to obtain the surplus military land, Carnall gave up his one-fourth stake in the venture. All public works had likely come under suspicion because of the 1871 federal Court of the Western District of Arkansas kickback scandal.

To make sure Congress would give the city the land, Carnall ended his contract with the city.

In 1890, he reflected in The Elevator:

“Though a great loss to me I feel fully compensated in the city’s great gain for the use of free public schools. Had it not been originated it never could have been consummated.”

These three historical biographies were researched for Gateway Park by Joe Wasson, who particularly appreciates John Carnall as a person and for the record left by Carnall’s many publications.