For most of his long career, Galen Hunter has adhered to the precision of architectural drawings.

As a principal of the Fort Smith firm MAHG, Hunter has led its design work for such works as the University of Arkansas – Fort Smith Bell Tower and Campus Green and many other familiar public buildings in Arkansas that have become visual symbols of their institutions.

A set of architectural drawings serves to describe a structure technically, instructing its construction.

All kinds of architectural drawings conform to conventions, whether for presentation renderings, site plans, blueprints or detail. Many of the drawings required of the architect are now produced digitally, rarely drafted by hand today.

But architecture is also a fine art, concerned with conveying beauty as well as function, expressing philosophical ideas. An architect has a high visual sensitivity and reacts to visual ideas, patterns and colors.

Recently, Hunter took up painting for pleasure, studying in Europe with teachers who led classes en plein air, “in the open air,” standing at an easel and painting or sketching while regarding one’s subject. The artist takes in the play of natural light and the surrounding environment upon the subject of an image.

A particular series of Hunter’s paintings captured the attention of the Fort Smith Museum of History, where Hunter’s work will be exhibited from April to October in the Boyd Gallery.

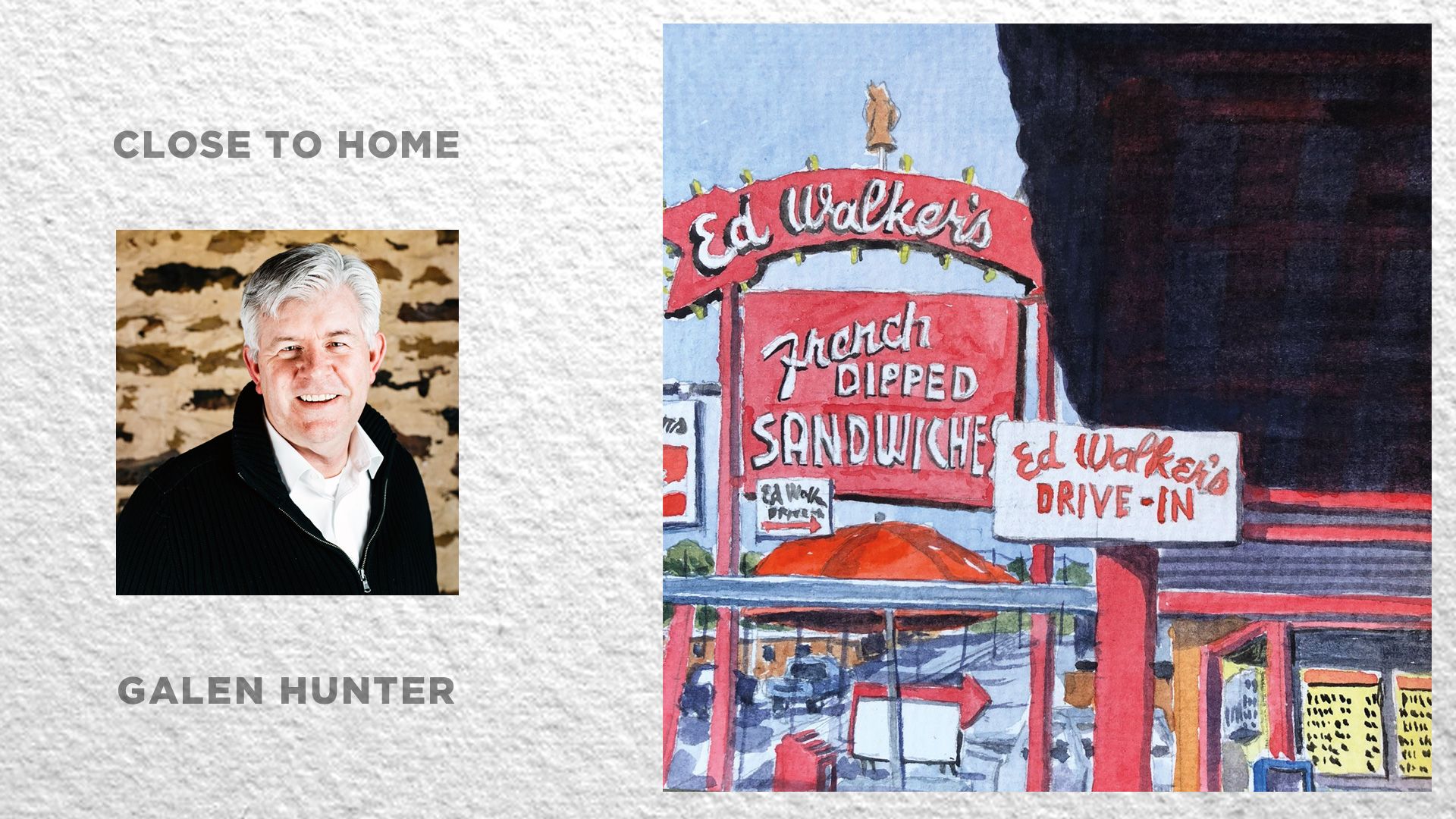

Hunter has been painting in and around his hometown, his eye attracted to humble places. It’s almost as if he chose the familiar, yet overlooked, as his subject for small watercolor paintings. Squat, cinderblock buildings on Towson Avenue that have changed business purposes year after year. Tire shops. Metal buildings. Diners. A locksmith shop on Rogers Avenue.

Caroline Speir, the executive director of the Fort Smith Museum of History, discovered Hunter’s paintings as he posted a few works in progress on Instagram.

“I completely fell in love,” she said. While she recognized many of the locations he had painted, “How many of them have you thought about in terms of art?” she mused. Hunter’s series, perhaps not by his intention, was documenting locations in Fort Smith and some nearby towns that are seen daily and have integral roles in the life of the city, but which are seldom photographed or memorialized.

“I think the word he used was ‘mundane,’” she said, while disagreeing. Collectively, these paintings prompt recognition, a sense of home, its workaday rhythms and one’s place in it.

As an exhibit designer, Speir had worked with Hunter in developing a prior exhibit for the museum that surveyed a 100-year history of the architecture firms of Fort Smith. While she then became executive director of the museum, she still has charge of that role.

The pandemic forced the museum to close to the public for part of 2020, making it difficult to plan for and create new, temporary exhibits for the Boyd Gallery, which have focused on contemporary connections to the community.

Speir has helped mount a popular, two-part exhibit called “The Music that Moved Fort Smith” and Black History exhibits, both of which attracted high engagement.

Hunter’s local paintings were interspersed with those of grand cathedrals and piazzas of Italy, quite a contrast.

He explained he has been able to spend a week, over the past few years, taking a painting class in Italy. He’d then join his wife for more time traveling in Europe, also painting along the way. It can only be called a target-rich environment.

But it is the experience of painting that pleases him, Hunter said. So while he was not able to go to Italy in 2020, he turned to what was within sight. When Speir invited him to mount an exhibition of the local paintings this spring, he focused his scope even more and has enjoyed himself, he said.

“The places here that I have been around for 60 years have much more meaning for me,” he admitted. “When they talk about writers should write what they know, I think it is the same for painting. The buildings here have such a story to them, because I remember what they were before what they are now.”

Structures, naturally, attract his attention but are approached in a painterly way. One of the teachers under whom he worked in his Italian sojourns is Stephanie Bower, an architectural illustrator based in Seattle. Another is Liz Steel of Sydney, Australia, herself an architect who has become a full-time artist and teacher.

Both he and they have spent a career familiar with the architectural renderings used in presentations to make a “hero” of a structure, which often do not include any other surrounding buildings or landscape.

These watercolors, painted on site, are quite different and much more authentic than those idealized depictions.

It’s a little hard to loosen up, Hunter said. “My training helps me to understand how buildings are put together.” While painting in this way, however, his eye and hand follow light and shadow and he includes real-life atmosphere, the clutter of unrelated signs and billboards, light poles or electrical wires. He has even stretched to include cars or in the case of these hometown paintings, “trucks, around here.” he laughed. He had to learn to draw vehicles.

He began drawing some of this series in pen-and-ink, but challenged himself to sketch only in pencil and then add watercolor. The result is softer and evokes emotional authenticity.

As an architect and a native, Hunter finds personal meaning and memory in some of the art. His look at Mid-Town Apartments incudes the knowledge it was once St. Edward’s Hospital; his brother was born there, he said. The Donut Palace, which he can recall as a Maytag store and a Senor Bob’s taco stand, is operated by a family whose life story he knows through the book Where the Wind Leads by Vihn Chung. It is an inspiring account of how Chung’s family fled South Vietnam by boat and worked very hard to make a new life here.

Hunter did not depict his own design work in the exhibit, although he or his firm have been responsible for many landmark projects, such as the Riverfront Parks complex of amphitheatre, events building and pavilion. His firm also designed the Fort Smith Public Library and branch libraries and had, historically, also designed the previous downtown library.

MAHG designed much of the present UAFS campus, most lately the expanded Boreham Library Learning & Research Center, in addition to its Campus Green, Bell Tower and Smith-Pendergraft Campus Center.

But collectively, in the vernacular buildings, alleys, doorways and details of Hunter’s series, you will recognize where you are, from downtown to the Van Buren Depot to the south side to Chaffee Crossing.

“Close to Home” opens with a reception at 6 p.m. April 1 at the Fort Smith Museum of History, 320 Rogers Avenue. Donations suggested. It will hang through Oct. 1. Current museum hours are 10 a.m.-4 p.m. Tuesday-Saturday.